Case 1: Cobalt Oxide Nanoparticles [prof. Joon T. Park’s group]

Example 1: The fcc CoO solid nanoparallelepipeds, are reduced by the oleylamine surfactant to form fcc Co hollow nanoparallelepipeds

A green slurry of [Co(acac)3] (0.10 g, 0.28 mmol) in neat oleylamine (9.24 mL) was heated at 135 °C for 5 min. Immediately after dissolution, the reaction mixture was flash-heated to 200 °C. After the solution was stirred at 200 °C for 1 h, hexagonal pyramid-shaped hcp CoO nanocrystals with side edge lengths of (47±4.6) nm and basal edge length of (24±2.4) nm were obtained as a green suspension. The green suspension was heated at 240 °C for 1 h to afford fcc CoO nanoparallelepipeds as a brown suspension. The resulting brown suspension of fcc CoO nanoparallelepipeds was heated at 290 °C for 2 h and 270 °C for 1 h to produce a black suspension. The black fcc Co hollow nanoparallelepipeds were separated by centrifugation and purified by washing with ethanol.

Angewandte Chemie International Edition 47.49 (2008): 9504-9508

Figure 1. Evolution of fcc Co hollow nanoparallelepipeds with time. a) TEM image of fcc CoO nanoparallelepipeds. b,c) TEM images of nanoparallelepipeds after heating fcc CoO at 290 °C for b) 1 h and c) 2 h; d) TEM image of fcc Co nanoparallelepipeds prepared after heating fcc CoO at 290 °C for 2 h and then at 270 °C for 1 h. [Angewandte Chemie International Edition 47.49 (2008): 9504-9508]

The reaction mechanism of reduction of fcc CoO in the presence of oleylamine could be assign to the reaction:

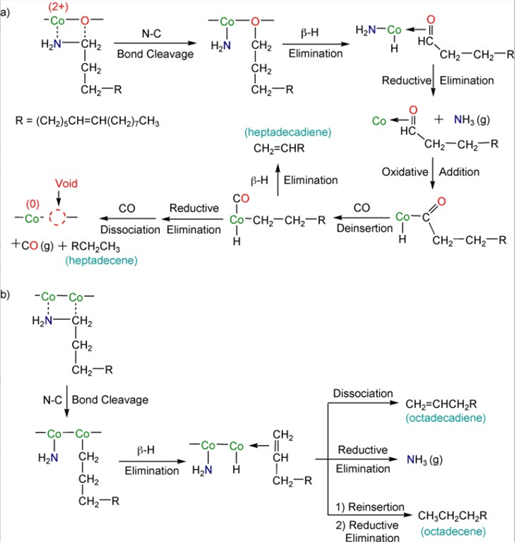

Plausible mechanism reaction pathways for the transformation are proposed in Scheme 1:

Scheme 1. Proposed reaction pathways: a) reduction of fcc CoO to fcc Co by oleylamine with formation of heptadecene and heptadecadiene; b) conversion of oleylamine into octadecene and octadecadiene by fcc Co.

Coordination of the amino group on the electropositive cobalt site and interaction of the relatively electropositive α-carbon atom of oleylamine with the oxygen center results in the C-N bond cleavage of oleylamine. This C-N bond cleavage of amines is known in catalytic hydrodenitrogenation reactions. The subsequent reaction sequences are well-documented reactions in organometallic chemistry, such as β-hydride elimination of the alkoxide, oxidative addition of C-N bonds, reductive elimination of NH3 and C17H34, and CO deinsertion and dissociation. The surface heptadecenyl species undergoes β-H elimination to produce the heptadecadiene. Overall, the fcc CoO has been reduced to fcc Co by oleylamine, which is oxidized to afford CO, NH3, and heptadecene. Voids are formed on the surface of fcc CoO solid nanoparallelepipeds by oxide removal. Octadecene (C18H36) and octadecadiene (C18H34) were also formed along with heptadecene and heptadecadiene during the conversion of fcc CoO to fcc Co from the reaction of fcc Co with oleylamine. The deamination of oleylamine followed by β-hydride and reductive eliminations of surface species on fcc Co proposed in Scheme 1b would produce ammonia and a mixture of octadecene and octadecadiene.

Proposing the definitive pathways for the formation of hollow fcc Co nanoparallelepipeds is not warranted, but it is likely that the hollow fcc Co nanoparallelepipeds would be generated by continuous diffusion of oxides out to the surface void followed by removal as carbon monoxide and simultaneous electron transfer from the surface Co atoms to the inner Co2+ ions to form surface Co2+ ions and interior Co atoms. This proposal is favored, since both the size and shape of the fcc CoO nanoparallelepipeds are conserved in the hollow fcc Co nanoparallelepipeds. The Co metal layer formed on the surface in the early stage determines the size and shape of the hollow fcc Co nanoparallelepipeds, and the surface voids diffuse into the interior of the nanoparallelepipeds to result in the spherical shaped void, which is entirely due to the loss of oxides. The oxide diffusion is well known in metal oxides at high temperatures. Our observation is in contrast with the Kirkendall effect, in which the out-diffusion of one constituent is faster than the in-diffusion of the other, forming either a hollow compound or a hollow solid solution.

Example 2: Phase- and Size-Controlled Synthesis of Hexagonal and Cubic CoO Nanocrystals

Rod-shaped CoO nanocrystal: A green slurry of Co(acac) 3 (0.05 g, 0.14 mmol) and oleylamine (7.51 g, 28.07 mmol, 200 equiv) in a 100 mL Schlenk flask connected to a bubbler was heated at 135 °C for ca. 5 min under an argon atmosphere to give a clear green solution. Immediately after dissolution, the reaction was initiated by flash-heating in a heating mantle preheated at 200 °C. After the solution was annealed for 1 h, the reaction mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature giving a green suspension

Hexagonal pyramid shaped CoO nanocrystals: A similar procedure for the preparation of rod-shaped nanocrystals was used using Co(acac)3 (0.10 g, 0.28 mmol or double) and oleylamine (7.51 g, 28.07 mmol, 100 equiv)

Cubic CoO nanocrystals: A green slurry of Co(acac)3 (0.05 g, 0.14 mmol) and oleylamine (7.51 g, 28.07 mmol, 200 equiv) in a 100 mL Schlenk flask connected to a bubbler was heated at 135 °C under an argon atmosphere. The green reaction mixture gradually changed red in ca. 30 min; heating was maintained at 135 °C for 5 h. The resulting red solution was flash-heated to 200 °C by way of a preheated heating mantle. After the solution was annealed for 3 h, the reaction mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature to form a brown suspension, and the light yellow supernatant was removed by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes. Result is 13nm CoO cubic. To synthesize 24 nm CoO or 33nm CoO, the amount of Co(acac)3 need to be double or quadruple.

J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 17, 6188–6189

Figure 2. Evolution of fcc Co hollow nanoparallelepipeds with time. a) TEM image of fcc CoO nanoparallelepipeds. b,c) TEM images of nanoparallelepipeds after heating fcc CoO at 290 °C for b) 1 h and c) 2 h; d) TEM image of fcc Co nanoparallelepipeds prepared after heating fcc CoO at 290 °C for 2 h and then at 270 °C for 1 h. [J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 17, 6188–6189]

Although the reduction mechanism leading from Co(III)(acac)3 to Co(II)O and the source of oxygen have not been clearly determined, oleylamine may act as the reductant and the CoO oxygen may originate from the acac ligand.

The successful isolation of both hexagonal and cubic CoO phases in our studies seems to be associated with formation of the kinetic and thermodynamic precursors leading to seeds of two different phases at higher temperatures. The green precursor believed to be Co(acac)3 may produce hexagonal seeds upon abrupt heating to 200 °C. On the other hand, the red precursor, presumably an oleylamine-substituted cobalt complex formed by prolonged heating at 135 °C, provides cubic seeds. Most cobalt amine complexes are known to have red color. It is worth mentioning that intermediate reaction times between 30 min and 3 h at 135 °C lead to mixtures of both hexagonal and cubic CoO nanocrystals

Example 3: The Role of Water for the Phase-Selective Preparation of Hexagonal and Cubic Cobalt Oxide Nanoparticlesls

[Co(acac)2] (0.14 g, 0.54 mmol) was added to benzylamine (5.8 g, 54 mmol, 100 equiv) in a round-bottomed flask (100 mL) equipped with a reflux condenser at 100 °C. The mixture was immediately heated to 200 °C by a heating mantle and allowed to stir at 200 °C for 1 h. After the reaction, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and the product was precipitated by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting particles were washed twice with ethanol (40 mL) and dried in vacuum for 24 h to yield hexagonal CoO nanoparticles as green powders in nearly quantitative yield. For cubic CoO nanoparticles, [Co(acac)2] and water (0.050 mL, 2.7 mmol, 5 equiv) were added together to benzylamine, and the other conditions were identical.

Chemistry–An Asian Journal 6.6 (2011): 1575-1581

Scheme 2. Phase-selective synthesis of hexagonal and cubic CoO nanoparticles with or without water.

Discussion

Comparison of Cobalt(II) and Cobalt(III) Precursors

Cubic CoO is thermodynamically more stable than the hexagonal CoO phase, and the reaction time, temperature, and amine concentrations are factors that influence reaction products. High temperatures with short reaction times yield the hexagonal phase and low temperatures with prolonged reaction times favor the cubic phase. Interestingly, the addition of o-dichlorobenzene alters the reaction conditions to the thermodynamically favored regime. However, the reaction mechanisms differentiating hexagonal and cubic CoO phases were not clearly resolved. Another complicated problem is the reduction of cobalt(III) to cobalt(II) during the reaction. It has been suggested that amine condensation can generate hydrogen gas, which reduces the cobalt center to cobalt(II).

On the other hand, for the reaction with the cobalt(II) precursor, [Co(acac)2], the oxidation state does not need to be changed and the reaction mechanism proceeds only through decomposition and condensation. The process of adding water is very simple and does not yield a mixture of both phases. These are the reasons that the phase-selective formation of CoO nanoparticles can be more clearly understood in the cobalt(II) system

Color Change of the Reaction Mixture during the Reaction

The color of the [Co(acac)2] solution is deep purple. When amine was added to the reaction mixture, the solution immediately changed to a pink slurry, which was indicative of the formation of cobalt–amine species. Heating to 200 °C changed the color from pink to red, presumably as a result of the generation of cobalt hydroxide species. In the Pourbaix diagram of a Co–NH3–H2O system, the most stable species existing in solution are cobalt hydroxides at pH 6–13. Note that cobalt hydroxides are often used as precursors for the formation of cobalt oxides. Co(OH)2 has an intense red color. The color change to red is observed for the synthesis of both hexagonal and cubic CoO nanoparticles. This red reaction mixture turned black in 10 minutes and gradually changed to green after an additional 5 minutes under the conditions without water. The black color is attributed to a mixture of residual red cobalt hydroxide species and newly formed green hexagonal CoO seeds. By the addition of water, the color of the mixture slowly changed to brown over 30 minutes, yielding a brown cubic CoO dispersion. The observation of the color change during the reactions reveals that the formation of both hexagonal and cubic CoO phases follow a similar sequence of reactions, from the cobalt precursor to cobalt–amine and cobalt hydroxide species, and eventually to the CoO phases. These cobalt–amine and hydroxide species, and related reaction kinetics, are crucial for the differentiation of hexagonal and cubic phases.

Gas Chromatographic Analysis of the Side Products

Analysis of the side products helps us to understand detailed formation mechanisms. The signals are assigned to the reference signals with possible side products as follows: benzylamine (1), N-isopropylidenebenzylamine (2), N-benzylacetamide (3), 4-benzylamino-3-penten-2-one (4), and N-benzylidenebenzylamine (5). Interestingly, four out of the five signals, 1, 2, 3 and 5, are identical in both reactions, but compound 4 is exclusively detected in the hexagonal CoO synthesis. The formation of 4 is nearly negligible in the cubic CoO synthesis, and thus gives the possibility to elucidate the formation mechanism of the cubic phase.

Figure 3. Gas chromatograms of the supernatants from the reaction mixture for the preparation of a) hexagonal and b) cubic CoO nanoparticles.

Formation Mechanism of Hexagonal CoO Nanoparticles

In this reaction, the oxygen source was essentially the carbonyl groups of the acac ligand. More than seven products were analyzed and two different pathways were proposed. Our suggestions of formation mechanisms of hexagonal CoO nanoparticles are shown in Scheme 3, based on the similar decomposition mechanism of [Fe(acac)3]. Pathway A is based on a combination of solvolysis and condensation. Benzylamine carries out a nucleophilic attack on one of the carbonyl carbon atoms in the acac ligand. It breaks the CC bond between the carbonyl carbon and the center carbon, and forms 3 and acetonate enolate through aminolysis. The synthesis of 3 from the decomposition of acetylacetone with benzylamine in an autoclave at 200 °C has been reported.12 Another benzylamine attacks the enolate carbon, and generates a hydroxyl group on the cobalt center. Both 3 and 2 are released into the reaction mixture. The resulting cobalt hydroxide species attack other cobalt compounds and form CoOCo bonds, and the continuous formation of the CoO bonds leads to the generation of CoO seeds.

Product 4 in the GC–MS data reveals the existence of a different route: pathway B. Benzylamine attacks the carbonyl carbon of the acac ligand, but in this pathway direct condensation occurs without breaking C-C bonds. The resulting 4-benzylamino-3-penten-2-one (4) is released and the remaining cobalt hydroxide species attack the other cobalt compounds, yielding the CoO phase. The significant difference between the reaction pathways A and B is whether C-C bond breaking takes place or not. Given that the abundance of compounds 2, 3, and 4 is at the same level, the formation of hexagonal CoO phase proceeds through both reaction pathways, that is, with and without C-C bond cleavage. Compound 5 is a condensation product of the two molecules of benzylamine.

Role of Water for the Formation of Cubic CoO Nanoparticles

As noted earlier, the signal for 4 was nearly negligible in the synthesis of cubic CoO nanoparticles. This indicates that pathway A, which involves C-C bond cleavage of the acac ligand, is a major and preferred route to synthesize the thermodynamically more stable cubic CoO phase, whereas pathway B does not occur in this reaction. The only difference between hexagonal- and cubic-phase synthesis is the addition of water, and thus, the existence of water in the reaction mixture may play a key role in the phase selection of the CoO nanoparticles. Scheme 3 is a representation of the reaction mechanism in the presence of water. Under the present basic reaction conditions, hydroxide ions are the major species and they attack a carbonyl carbon of the acac ligand because the hydroxide ions are a more nucleophilic Lewis base than benzylamine. By this strong nucleophilic attack, CC bond cleavage is the preferred pathway to form carboxylate and acetonate enolate ligands. It was reported that the decomposition of acac ligands in zinc acetylacetonate under basic conditions similarly generates carboxylate and hydroxide.15 The hydroxide ions also attack the enolate carbon, generating hydroxide on the cobalt center, and releasing acetone. The resulting products, carboxylate and acetone, undergo condensation with benzylamine to yield compounds 2 and 3. Consequently, compounds 2 and 3 are the only byproducts of the reaction sequence. It is well known that the carboxylate ligand is tightly bound to the metal center through chelation and stabilizes metal complexes.16 Accordingly, decomposition of the cobalt hydroxide intermediate is decelerated and the reaction enters the regime of thermodynamic control to yield cubic CoO nanoparticles.

Scheme 4. A plausible reaction pathway for the formation of cubic CoO nanoparticles in the presence of water.

Water also leads to the formation of cubic CoO nanoparticles from [Co(acac)3] and the mechanism may be similar to that of [Co(acac)2], with a combination of metal reduction either by amine itself or by hydrogen gas evolved from amine condensation.

In this CoO case, water effectively changes the crystallographic phase of the nanoparticles, but sometimes generates different oxidation compositions in other cases. For instance, the decomposition of [Mn(acac)2] yields Mn3O4 nanoparticles under well-controlled reaction conditions, but the addition of 10 equivalents of water exclusively generates MnO nanoparticles

Case 2: Cobalt Oxide Nanoparticles

40 and 75 nm (average edge length) CoO nanooctahedra were obtained using the hot-injection thermodecomposition of cobalt acetate (2.66 and 4 mmol) (dissolved in 5 mL of ethanol) in trioctylamine (25 mL, 57.18 mmol) and oleic acid (5.12 and 8 mmol) at 170 °C and then left to reflux (at T = 300 °C) for two hours. 20 nm (average edge length) CoO nanooctahedra were similarly synthesized dissolving cobalt acetate (2 mmol), oleic acid (8 mmol), oleylamine (20 mmol) and TOPO (0.2 mmol) in a mixture of trioctylamine (5 mL) and octyl ether (15 mL), and then heating to reflux (at T = 300 °C) for six hours. Once cooled to room temperature, the nanostructures were separated by centrifugation, washed several times, and finally stored in ethanol.

Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 2, 640–647

In comparison to previous work by Park and co-workers who synthesized hexagonal and cubic cobalt oxide nanoparticles and nanoparallelepipeds from a similar reaction (cobalt acetylacetonate in benzylamine or oleylamine, (26-28) instead of cobalt acetate in trioctylamine), our method is different in terms of (i) the nucleophilic attack between the acetate and the amine groups, (ii) the growth of the nanoparticles (using oleic acid), and (iii) the solvent that reaches a much higher refluxing temperature. All three aspects favor the production of perfectly shaped octahedra. Oleic acid as capping agent controls the formation of densely packed {111} facets, (29) because in its absence no octahedra were produced. For an understanding, one has to consider the surface energies and polarizabilities of different crystallographic facets of ionic crystals. (30, 31) The capping molecules with negatively charged head groups can selectively stabilize the (111) planes (containing Co2+ (or Co3+) cations only) because electrostatically the interaction with the charged {111} facets is favored in comparison to the uncharged {100} facets (containing Co and O atoms). The polar (111) surface is energetically not stable. Goniakowski et al. pointed out that nature tends to avoid such a polarity catastrophe by changing the distribution of surface charges or the modification of the composition of the surface region. (32) In our case, surface stabilization seems to be attained by the formation of the spinel Co3O4 configuration, which can be seen as four layers of a hypothetical spinel (with three out of four top oxygen atoms missing) on top of CoO. Similarly to an O-terminated octopolar configuration, the spinel-like termination is characterized by three-fourths of the oxygens missing in the surface layer and one-fourth of the cations missing in the subsurface layer and thus fulfills the electrostatic compensation condition. A chemical stabilization of the surface facets by OH groups can also be considered.

Figure 4. HRTEM (a, left) and 3D reconstruction images (a, right, and b–d) of the octahedra

Figure 4d shows the oblique slicing along an octahedron [001] zone-axis, which reveals some voids inside the octahedron (indicated by black arrows), also appreciated in some TEM images. The presence of holes inside the octahedra and located around a main and centered cavity (5–10 nm in diameter) can be explained considering the synthetic process as kinetically controlled (nucleation at T ∼ 170 °C). In that case, an organometallic intermediate phase would match the premises for creating some kind of porosity using a chemical gradient, because according to Smigelkas and Kirkendall solid diffusion in a concentration gradient occurs through a vacancy exchange mechanism. (33) If the diffusion coefficient of the two species (the intermediate organometallic compound and the CoO) is different, the net directional flow of vacancies results in the formation of pores with the outward diffusion of the core material (the intermediate organometallic compound) through the CoO being faster than the inward diffusion of the outer material (the CoO). Gösele and co-workers claimed a general fabrication route for hollow nanostructures provided that the Kirkendall effect should be generic, (34, 35) and Dilger et al. reported a similar case for the synthesis of aerogel-like ZnO with organometallic methylzinc methoxyethoxide ([MeZnOEtOMe]4) and ZnO.

Ethan Savette

Product Designer at Idea, Ethan’s work has been featured as pioneer in CX as best practice.

Ray Cordova

UX Manager at Clockwork. He formerly pioneered the Design System at Blue Sun, and led the Moonlight at Wonders and Co.

Leave a comment