The paper I read in this post:

- Multicomponent equiatomic rare earth oxides (ME-REO) with a narrow band gap and associated praseodymium multivalency (Dalton Trans., 2017,46, 12167-12176 DOI https://doi.org/10.1039/C7DT02077E)

- Improving the Activity for Oxygen Evolution Reaction by Tailoring Oxygen Defects in Double Perovskite Oxides (The Role of Oxygen Vacancy in Determining the OER Performance https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/adfm.201901783 Adv. Funct. Mater.2019, 29, 1901783)

- Band Gap Narrowing in a High-Entropy Spinel Oxide Semiconductor for Enhanced Oxygen Evolution Catalysis (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 12, 6753–6761 https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c12887)

Example 1: Tailoring Oxygen Defects in Double Perovskite Oxides

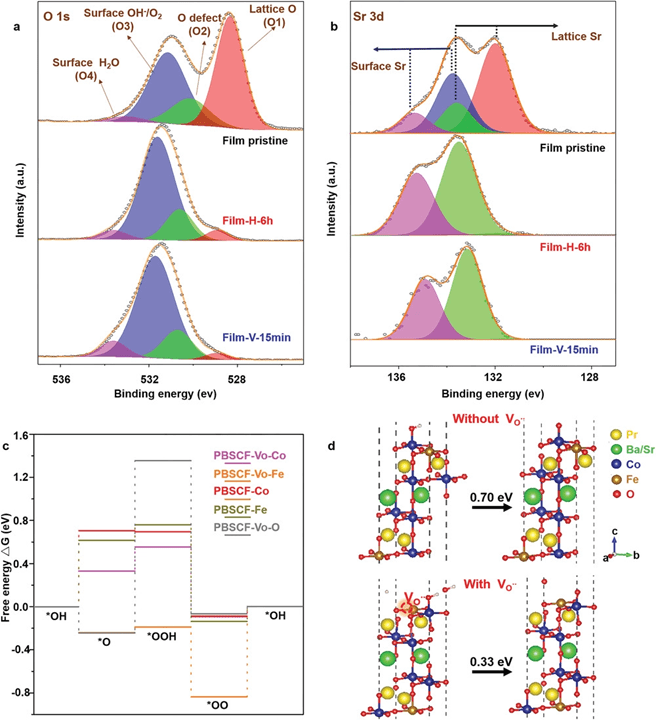

The authors tailored oxygen defects in Double Perovskite Oxides PrBa0.5Sr0.5Co1.5Fe0.5O5+δ (PBSCF) by thermal annealing (at 400 °C in 1 atm H2 gas atmosphere, sample #H) or electrochemical reduction (negative bias of −1.0 V vs Ag/AgCl, sample #V). The surface of PBSCF thin film remained very smooth after thermal annealing and electrochemical reduction (Figure S1c, Supporting Information), with a surface roughness of less than 1 nm.

Figure 1. a,b) XPS spectra of a) O 1s, and b) Sr 3d of the pristine PBSCF film, Film-H-6h and Film-V-15 min. c) The computed Gibbs free energy diagram of the four-step 4e− OER mechanism on PBSCF slab with and without one surface vacancy. The adsorption sites investigated include the Co and Fe sites for PBSCF, the Co, Fe, and Vo sites for PBSCF with oxygen vacancy (PBSCF-Vo). d) Atomic structures of PBSCF slabs with adsorbates on the Co site with and without oxygen vacancy presented. The free energy changes of the *OH−*O step with and without induced defect are marked.

I. Why do oxygen vacancies have linear relationship with band gap narrowing?

Oxygen vacancies are frequently associated with band gap narrowing in many oxides, including CeO2.32 Therefore, considering a perfect fluorite structure, like CeO2, the presence of oxygen defects could be the possible reasons for the observed band gap narrowing in (RE)O2−δ. The formation of oxygen vacancies in ME-REOs can be attributed to the fact that except for Ce4+ and Pr3+/4+, all other rare earth cations are present in the 3+ oxidation state. In order to maintain the charge balance, oxygen vacancies are created according to the following defect formation reaction written in the Kröger–Vink notation (M′RE – RE3+ on the RE4+ site; O ×O – oxygen on the oxygen site, no charge):

As all the cations are in equiatomic proportions, the concentration of oxygen vacancies is much higher than in any of the doped or non-stoichiometric binary rare oxides. In order to understand if the oxygen vacancies could be responsible for this significant band gap lowering, the amounts of oxygen vacancies are estimated using the following considerations: (i) RE3+ and RE4+ exclusively form (RE)2O3 and (RE)O2, respectively, where the oxygen stoichiometry (x) in (RE)2O3 is 1.5 and in (RE)O2 is 2 and (ii) (RE)O2−δ systems contain RE elements in both 3+ and 4+ oxidation states (Ce4+, Gd3+, La3+, Nd3+, Pr4+/3+, Sm3+, and Y3+). Thus, the oxygen stoichiometry in (RE)O2−δ can then be expressed as:

x = 1.5·[RE3+] + 2·[RE4+]

where [RE3+] and [RE4+] are the molar fractions of RE cations in 3+ and 4+ oxidation states, respectively. Therefore, the deviation from stoichiometry, i.e., the amount of oxygen vacancies (δ) can be estimated from:

δ = 2 − x

Tips: to calculate lattice parameter and cationic radii, read Dalton Trans., 2017,46, 12167-12176 DOI https://doi.org/10.1039/C7DT02077E

II. Why do oxygen vacancies have linear relationship with band gap narrowing?

The narrowing of the band gap, in several systems, is often related to the formation of intermediate energy states due to the presence of point defects, like oxygen vacancies. The same is likely true for ME-REOs, especially considering the high amount of oxygen vacancies present in these systems. Interestingly, the change in the band gap values in ME-REOs is not directly related to the change in the amount of oxygen vacancies (compare Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, in oxide systems, like CeO2 or TiO2, where oxygen vacancies are often identified as the reason for the band gap narrowing, a decrease of band gap energy by only 0.32 eV or 0.30 eV,44 respectively, is observed. However, considering CeO2 as the parent structure of ME-REOs, the extent of the band gap narrowing in ME-REOs is more than 1 eV, which indicates that some additional factors other than oxygen vacancies are likely involved in the band gap narrowing.

The presence of certain multivalent elements is known to have a strong impact on the band gap, and hence, the light absorption behavior, in some systems, like Cu doped ZnO and Pr doped CeO2. In the case of ME-REOs, the presence of Pr in a multivalent state can be one of the reasons for the observed band gap narrowing. To ensure the validity of this reasoning, three different ME-REO systems without Pr (i.e., (Ce,La,Sm)O2−δ, (Ce,La,Sm,Y)O2−δ and (Ce,La,Nd,SmY)O2−δ) are synthesized. The XRD analysis (see ESI, Fig. S2-a† and the related discussion) shows that these systems are phase pure and also have a fluorite type of structure just like the ME-REOs with Pr. However, the band gap values (see ESI, Fig. S2b†) of these three ME-REO systems (without Pr) are in the range of 2.90–3.05 eV, i.e., around 1 eV higher than the ME-REO systems with Pr. The band gap values of these three systems are also close to that of CeO2 (3.2 eV) and the small difference in the values (0.30–0.15 eV) is related to the oxygen defects present in the systems. Hence, it is concluded that Pr plays a dominant role in the band gap narrowing of ME-REOs.

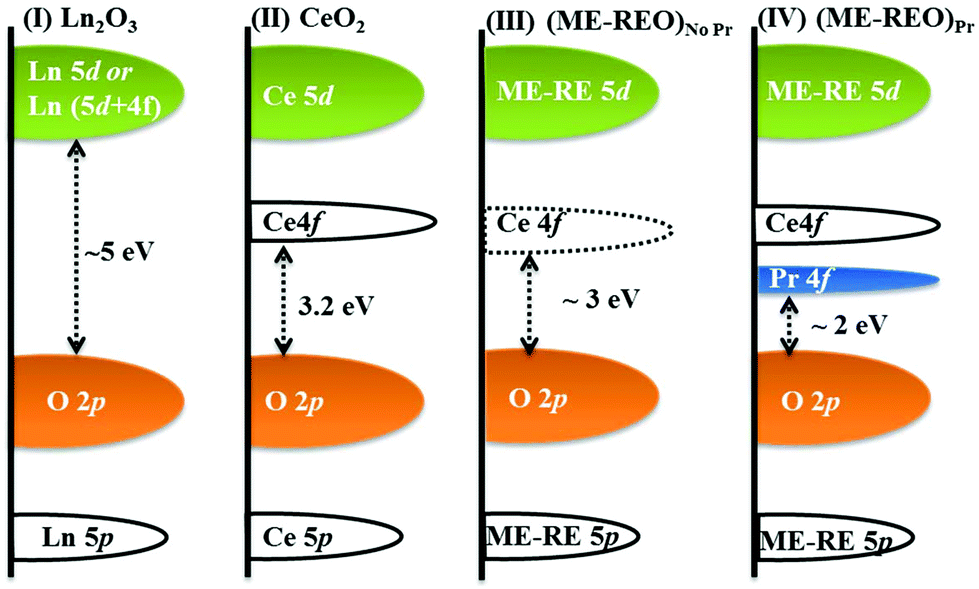

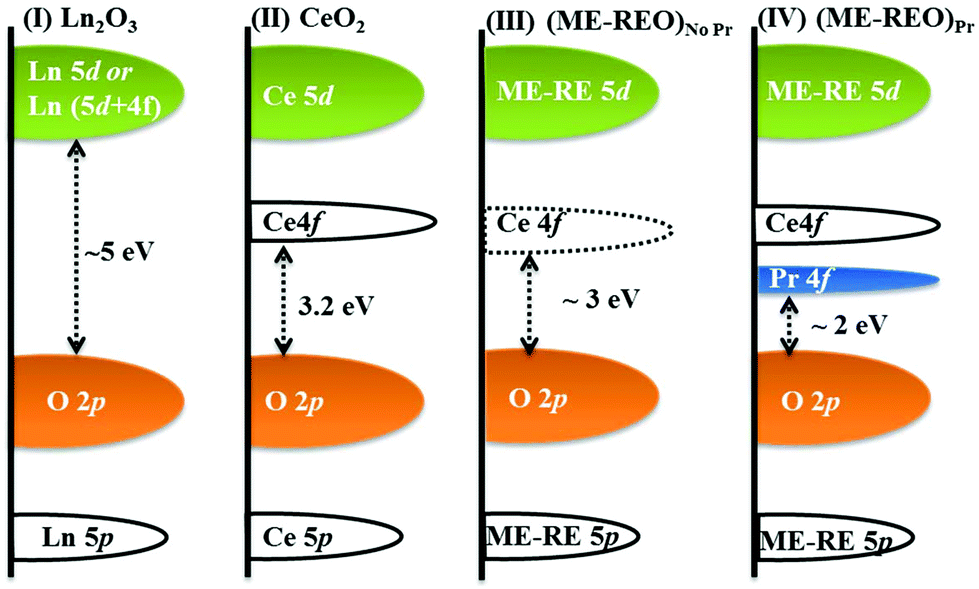

Based on these results, a possible schematic of the band structure of ME-REOs (Figure 1) is discussed in the following lines. In rare earth oxides, most of the RE elements have their O 2p and RE 5d energy levels at relatively similar positions. However, the position of occupied and unoccupied RE 4f energy bands, which are located in between O 2p and RE 5d energy bands, plays a crucial role in determining the type of electronic transition and, therefore, the band gap value. In most of the RE sesquioxides, the band gap values are related to electronic transitions from O 2p to RE 5d or 5d + 4funoccupied energy bands (as in La2O3 or Sm2O3, respectively),as shown in Figure 1, case I. The 5d + 4funoccupied is relevant for those lanthanides whose unoccupied 4f bands fall into the 5d energy band. The electronic transitions in the case of CeO2 occur from the O 2p to Ce 4f energy level (see Figure 1, case II) and these transitions are activated due to the inherent oxygen vacancies present in ceria. In ME-REOs without Pr, the electronic transitions are possibly very similar to that in ceria, while the presence of oxygen vacancies might have narrowed down the gap between the O 2p and Ce 4f energy levels (see Figure 1, case III). In Pr substituted CeO2 systems, it is believed that an additional Pr 4f band, between the O 2p and Ce 4f, is present. The same is likely to be true for ME-REOs with Pr. Thus, the band gap of ∼2 eV in ME-REOs with Pr can be related to the electronic transition between the O 2p to Pr 4f, which lies at ∼1 eV (ref. 49) below the Ce 4f energy band (see Figure 1, case IV).

Figure 1. Schematic of the band structures of Ln2O3, where Ln = Gd3+, La3+, Sm3+, etc. (case I), CeO2 (case II), ME-REOs without Pr (case III) and ME-REOs with Pr (case IV), depicting the possible mechanism for band gap narrowing.[Dalton Trans., 2017,46, 12167-12176]

III. High-Entropy Spinel Oxide with Band Gap of 0.9 V

This unexpected finding can be understood as resulting from shifted d-band energies. Previous computational work on Fe, Co, or Ni doping of CuAl2O4 demonstrates that all three of these metals contributed to the density of states just above the Fermi level. In the high-entropy A5Al2O4 spinel, it is expected that the conduction band will be significantly influenced by the five constituent metals. DFT calculations predict that the binary alloys have a smaller band gap energy than the end members, with a few exceptions that may be an artifact of the specific configurations studied. This is caused by the differing electronegativities, χ, and crystal field splitting, Δ, of the dopant and host transition-metal cations, as shown in Figure 2a. These differences introduce 3d states within the band gap of the host material, as depicted schematically in Figure 2b. Additionally, transition metal dopants having lower Δ can also affect the band gap by reducing the crystal field splitting of the host transition metal; in practice, this lowers the energy of unoccupied t2g states and consequently the band gap energy, as seen in Figure 2c. The intensity of this effect increases with the difference between the crystal field splitting of the host and dopant transition metal. Further, increasing the fraction of the transition metal with lower crystal field splitting causes this effect to be more pronounced. Interestingly, the two mechanisms of band gap reduction can produce two different types of transitions (i.e., bonding-to-antibonding and antibonding-to-antibonding electron transfer) depending on the 3d states from which the band edges originate

Figure 2. (a) Trends in crystal field splitting Δ and electronegativity χ for the five constituent metals of the high-entropy spinel. Crystal field splitting for tetrahedrally coordinated divalent Co and Cu. (b) The addition of a transition metal of greater electronegativity can reduce the band gap energy by introducing states between the eg and t2g states of the original transition metal. (c) The addition of a transition metal of lower crystal field splitting can reduce the band gap energy both by introducing new occupied t2g states above the eg states of the original transition metal and by lowering its unoccupied t2g states.[J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 6753−6761]

The paper I read in this post:

- Oxygen evolution reaction: a perspective on a decade of atomic scale simulations (DOI: 10.1039/C9SC05897D (Edge Article) Chem. Sci., 2020, 11, 2943-2950)

I. Fundamental

1.1. Equation of OER

The HER has minor losses compared to the complementary reaction at the anode, the Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER). This is the bottleneck of the overall reaction of water splitting because of the high required driving force. Numerous experimental and theoretical studies have been conducted, trying to lower the overpotential needed for the reaction of water oxidation and thus increasing the efficiency of the overall reaction. The half-reaction describing the OER is as follows:

2H2O → O2 + 4(H+ + e−) (3)

The reaction consists of four consecutive electrochemical steps and the simplest way of conceiving that is by a reaction proceeding via three surface bound intermediates.

H2O + * → HO* + H+ + e− (4)

HO* → O* + H+ + e− (5)

H2O + O* → HOO* + H+ + e− (6)

HOO* → * + O2 + H+ + e− (7)

In eqn (4)–(7), represents an active surface site and HO*, O*, and HOO* are the reaction intermediates adsorbed on the active sites of the catalyst. This reaction pathway is valid for acidic media; however from the thermodynamic perspective, changing to an alkaline medium does not change the analysis.

The overpotential seems to be an intrinsic property of the OER resulting from the constant energy difference between the HO* and HOO* intermediates, the so-called universal scaling relationship. The constant energy difference is a consequence of the similar way these particular intermediates are adsorbed on a surface, namely by creating a single bond between O and the active site. The energetic relationship for HO* and HOO* is

ΔEHOO* = ΔEHO* + (3.2 ± 0.2) eV

while for the ideal situation, it is ΔEHOO* = ΔEHO* + 2.46 eV.

Thus, the constant difference between HOO* and HO* defines an upper limit for how efficient an OER catalyst can be, while fulfilling the scaling relationship. It seems that all OER catalysts are subject to this limitation.

Assuming that the HO/HOO relationship has to be accepted as a precondition, the binding of O, which is the intermediate in-between HO and HOO, has to be just right in order to reduce the overpotential as much as possible, and thus the energy difference between O and HO* can be used as a descriptor for the energy efficiency of the OER catalyst and can be used as a first criterion for identifying promising catalysts.

1.2. Binding of O* on a surface

The Fermi level of a semiconductor is located in the band gap, and thus adding or removing electrons from the system by doping with atoms with a different valence than that of the host will shift the Fermi level towards the conduction or the valence band respectively. In contrast, the Fermi level of a conductor will stay unaffected by a change of the number of electrons. Almost all simulations of doped oxides only include a single dopant.

Figure 1. Energy diagram for intermediates HO* and O*: (a) 0 dopants, (b) 1 dopant and (c) 2 dopants[Chem. Sci., 2020,11, 2943-2950]

One possible explanation for the slope of the O* trend line being close to 1 for doped structures is that including a single dopant results in a finite size effect that does not display the behavior of a real catalyst. A single dopant, most of the time, will provide only one electron available in the conduction band, which is used by the first bond created between the intermediate and the surface. When the double bond is formed, going from HO* to O*, the second electron is not available at the same chemical potential, and therefore it has to be taken from the valence band, see Figure 1b. In this case, O* binding to the surface is not affected by the changes of doping twice as pronounced as HO*, since the two electrons participating in the bond to O* come from two different chemical potentials.

As only the first electron in the oxygen bond comes from the conduction band and the second from the valence band, the oxygen bond has a dependence of EO* = Ec + Ev, see Table 1. Since the position of the valence band of a given material does not change, when changing the type of dopant, Ev is kept constant and the oxygen bond, therefore, is affected by the changes in the dopant with the same strength as HO* and HOO*, giving a scaling factor of 1. This finite size effect is therefore also partly responsible for the large scatter of the O* binding, as some of the data include both doped and non-doped structures.

Table 1. Intermediate energy dependence for three scenarios with 0, 1 or 2 dopants, depending either on Ev (valence band energy) or Ec (conduction band energy)

| Intermediate energy dependence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 dopants | 1 dopant | 2 dopants | |

| HO* | Ev | Ec | Ec |

| O* | 2Ev | Ec + Ev | 2Ec |

| HOO* | Ev | Ec | Ec |

The paper I read in this post:

- Multicomponent equiatomic rare earth oxides (ME-REO) with a narrow band gap and associated praseodymium multivalency (Dalton Trans., 2017,46, 12167-12176 DOI https://doi.org/10.1039/C7DT02077E)

- Improving the Activity for Oxygen Evolution Reaction by Tailoring Oxygen Defects in Double Perovskite Oxides (The Role of Oxygen Vacancy in Determining the OER Performance https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/adfm.201901783 Adv. Funct. Mater.2019, 29, 1901783)

- Band Gap Narrowing in a High-Entropy Spinel Oxide Semiconductor for Enhanced Oxygen Evolution Catalysis (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 12, 6753–6761 https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c12887)

I. Why do oxygen vacancies have linear relationship with band gap narrowing?

Oxygen vacancies are frequently associated with band gap narrowing in many oxides, including CeO2.32 Therefore, considering a perfect fluorite structure, like CeO2, the presence of oxygen defects could be the possible reasons for the observed band gap narrowing in (RE)O2−δ. The formation of oxygen vacancies in ME-REOs can be attributed to the fact that except for Ce4+ and Pr3+/4+, all other rare earth cations are present in the 3+ oxidation state. In order to maintain the charge balance, oxygen vacancies are created according to the following defect formation reaction written in the Kröger–Vink notation (M′RE – RE3+ on the RE4+ site; O ×O – oxygen on the oxygen site, no charge):

As all the cations are in equiatomic proportions, the concentration of oxygen vacancies is much higher than in any of the doped or non-stoichiometric binary rare oxides. In order to understand if the oxygen vacancies could be responsible for this significant band gap lowering, the amounts of oxygen vacancies are estimated using the following considerations: (i) RE3+ and RE4+ exclusively form (RE)2O3 and (RE)O2, respectively, where the oxygen stoichiometry (x) in (RE)2O3 is 1.5 and in (RE)O2 is 2 and (ii) (RE)O2−δ systems contain RE elements in both 3+ and 4+ oxidation states (Ce4+, Gd3+, La3+, Nd3+, Pr4+/3+, Sm3+, and Y3+). Thus, the oxygen stoichiometry in (RE)O2−δ can then be expressed as:

x = 1.5·[RE3+] + 2·[RE4+]

where [RE3+] and [RE4+] are the molar fractions of RE cations in 3+ and 4+ oxidation states, respectively. Therefore, the deviation from stoichiometry, i.e., the amount of oxygen vacancies (δ) can be estimated from:

δ = 2 − x

Tips: to calculate lattice parameter and cationic radii, read Dalton Trans., 2017,46, 12167-12176 DOI https://doi.org/10.1039/C7DT02077E

II. Why do oxygen vacancies have linear relationship with band gap narrowing?

The narrowing of the band gap, in several systems, is often related to the formation of intermediate energy states due to the presence of point defects, like oxygen vacancies. The same is likely true for ME-REOs, especially considering the high amount of oxygen vacancies present in these systems. Interestingly, the change in the band gap values in ME-REOs is not directly related to the change in the amount of oxygen vacancies (compare Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, in oxide systems, like CeO2 or TiO2, where oxygen vacancies are often identified as the reason for the band gap narrowing, a decrease of band gap energy by only 0.32 eV or 0.30 eV,44 respectively, is observed. However, considering CeO2 as the parent structure of ME-REOs, the extent of the band gap narrowing in ME-REOs is more than 1 eV, which indicates that some additional factors other than oxygen vacancies are likely involved in the band gap narrowing.

The presence of certain multivalent elements is known to have a strong impact on the band gap, and hence, the light absorption behavior, in some systems, like Cu doped ZnO and Pr doped CeO2. In the case of ME-REOs, the presence of Pr in a multivalent state can be one of the reasons for the observed band gap narrowing. To ensure the validity of this reasoning, three different ME-REO systems without Pr (i.e., (Ce,La,Sm)O2−δ, (Ce,La,Sm,Y)O2−δ and (Ce,La,Nd,SmY)O2−δ) are synthesized. The XRD analysis (see ESI, Fig. S2-a† and the related discussion) shows that these systems are phase pure and also have a fluorite type of structure just like the ME-REOs with Pr. However, the band gap values (see ESI, Fig. S2b†) of these three ME-REO systems (without Pr) are in the range of 2.90–3.05 eV, i.e., around 1 eV higher than the ME-REO systems with Pr. The band gap values of these three systems are also close to that of CeO2 (3.2 eV) and the small difference in the values (0.30–0.15 eV) is related to the oxygen defects present in the systems. Hence, it is concluded that Pr plays a dominant role in the band gap narrowing of ME-REOs.

Based on these results, a possible schematic of the band structure of ME-REOs (Figure 1) is discussed in the following lines. In rare earth oxides, most of the RE elements have their O 2p and RE 5d energy levels at relatively similar positions. However, the position of occupied and unoccupied RE 4f energy bands, which are located in between O 2p and RE 5d energy bands, plays a crucial role in determining the type of electronic transition and, therefore, the band gap value. In most of the RE sesquioxides, the band gap values are related to electronic transitions from O 2p to RE 5d or 5d + 4funoccupied energy bands (as in La2O3 or Sm2O3, respectively),as shown in Figure 1, case I. The 5d + 4funoccupied is relevant for those lanthanides whose unoccupied 4f bands fall into the 5d energy band. The electronic transitions in the case of CeO2 occur from the O 2p to Ce 4f energy level (see Figure 1, case II) and these transitions are activated due to the inherent oxygen vacancies present in ceria. In ME-REOs without Pr, the electronic transitions are possibly very similar to that in ceria, while the presence of oxygen vacancies might have narrowed down the gap between the O 2p and Ce 4f energy levels (see Figure 1, case III). In Pr substituted CeO2 systems, it is believed that an additional Pr 4f band, between the O 2p and Ce 4f, is present. The same is likely to be true for ME-REOs with Pr. Thus, the band gap of ∼2 eV in ME-REOs with Pr can be related to the electronic transition between the O 2p to Pr 4f, which lies at ∼1 eV (ref. 49) below the Ce 4f energy band (see Figure 1, case IV).

Figure 1. Schematic of the band structures of Ln2O3, where Ln = Gd3+, La3+, Sm3+, etc. (case I), CeO2 (case II), ME-REOs without Pr (case III) and ME-REOs with Pr (case IV), depicting the possible mechanism for band gap narrowing.[Dalton Trans., 2017,46, 12167-12176]

III. High-Entropy Spinel Oxide with Band Gap of 0.9 V

This unexpected finding can be understood as resulting from shifted d-band energies. Previous computational work on Fe, Co, or Ni doping of CuAl2O4 demonstrates that all three of these metals contributed to the density of states just above the Fermi level. In the high-entropy A5Al2O4 spinel, it is expected that the conduction band will be significantly influenced by the five constituent metals. DFT calculations predict that the binary alloys have a smaller band gap energy than the end members, with a few exceptions that may be an artifact of the specific configurations studied. This is caused by the differing electronegativities, χ, and crystal field splitting, Δ, of the dopant and host transition-metal cations, as shown in Figure 2a. These differences introduce 3d states within the band gap of the host material, as depicted schematically in Figure 2b. Additionally, transition metal dopants having lower Δ can also affect the band gap by reducing the crystal field splitting of the host transition metal; in practice, this lowers the energy of unoccupied t2g states and consequently the band gap energy, as seen in Figure 2c. The intensity of this effect increases with the difference between the crystal field splitting of the host and dopant transition metal. Further, increasing the fraction of the transition metal with lower crystal field splitting causes this effect to be more pronounced. Interestingly, the two mechanisms of band gap reduction can produce two different types of transitions (i.e., bonding-to-antibonding and antibonding-to-antibonding electron transfer) depending on the 3d states from which the band edges originate

Figure 2. (a) Trends in crystal field splitting Δ and electronegativity χ for the five constituent metals of the high-entropy spinel. Crystal field splitting for tetrahedrally coordinated divalent Co and Cu. (b) The addition of a transition metal of greater electronegativity can reduce the band gap energy by introducing states between the eg and t2g states of the original transition metal. (c) The addition of a transition metal of lower crystal field splitting can reduce the band gap energy both by introducing new occupied t2g states above the eg states of the original transition metal and by lowering its unoccupied t2g states.[J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 6753−6761]

Leave a comment